Get in touch

-

Additional Tax Relief available for “R&D Intensive” SMEs

Consulting

News Article

Find out more about the enhanced tax relief that R&D-intensive, loss-making SMEs will receive under the new merged R&D tax relief scheme introduced by the Government on April 1st 2024. Read on...

12 April 2024

-

Advancements in Additive Manufacturing for Aerospace Components

Innovation & New Technology

Consulting

News Article

14 March 2024

With every material breakthrough, every design innovation, and every step towards more sustainable manufacturing practices, Additive Manufacturing reaffirms its role as a cornerstone of aerospace engineering and manufacturing.

-

Finance Act 2024 - Impact of new R&D tax legislation

Consulting

News Article

29 February 2024

The biggest shake-up to the R&D tax scheme since its inception is now consecrated in law. The rules governing the single RDEC scheme and the R&D Intensive SME scheme are now set in legislation. Although the new schemes do result in some minor simplifications, these rules also bring about complexities that we advise companies to seek immediate professional advice on. Read on...

-

Capital RDAs or Capital Allowances? A Guide to Maximising the Allowances on Offer

Consulting

News Article

19 February 2024

Following recent changes both to the R&D tax relief scheme and to Capital Allowances, many companies are confused about which pot to claim from, in order to maximise the tax breaks they can take advantage of. Our Guide to Maximising the Allowances on Offer is worth a read if you undertake R&D

-

SOLIDWORKS Generates Positive Reaction at MoltexFLEX

Solutions

Case Study

16 February 2024

MoltexFLEX, has been diligently crafting the 'Flex Reactor', a graphite moderative marvel poised for mass deployment and ready to disrupt fossil fuel dominance. We visited the team to find out how SOLIDWORKS has helped them develop their game changing green technology...

-

March Year End: Fail to Prepare, Prepare to Fail

Consulting

News Article

18 January 2024

Read our guide for a reminder to secure your claims before the deadline and also to find out more about how to prepare for the upcoming changes in R&D tax incentives.

-

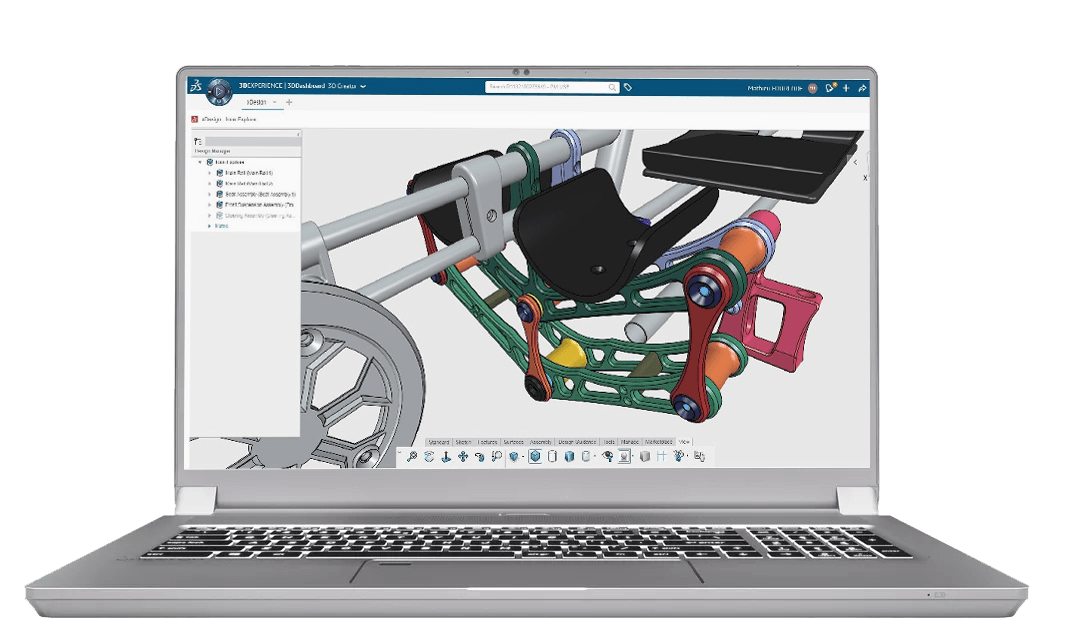

SOLIDWORKS 2024: Top 10 Enhancements

Solutions

Resources & Tutorials

15 January 2024

Ease-of-use has been a cornerstone of the SOLIDWORKS experience from day one. SOLIDWORKS 2024 continues this tradition, incorporating user feedback into enhanced functionalities and time saving features. Applications Engineer, Sam Barlow, picks out ten of the best...